CBSA wants to hide identities of undercover officers who investigated man accused of plotting Toronto attacks

Should Canada deport accused terrorists without trial?

March 12, 2015Malik v. Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2015 CanLII 66230 (CA IRB)

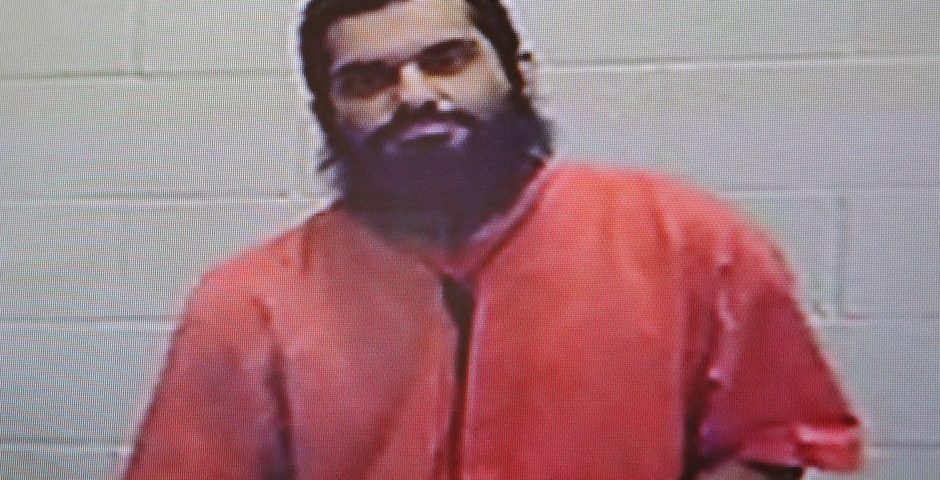

June 5, 2015Jahanzeb Malik, 33, is seen on a videolink from his cell in Lindsay, Ont., at an immigration detention review in Toronto on Monday, March 16, 2015. Malik is accused of planning to blow up the U.S. consulate and downtown buildings in Toronto and will likely be deported to Pakistan. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Colin Perkel

Federal officials are seeking to hide the identities of the undercover officers involved in the investigation that led to the arrest of a Pakistani man accused of plotting to bomb the United States consulate in Toronto.

The Canada Border Services Agency intends to ask the Immigration and Refugee Board, which is hearing the case against Jahanzeb Malik, to ban media outlets from publicly identifying the officers, the suspect’s lawyer Anser Farooq said Sunday.

He said he had received a two-page letter from the CBSA informing him of the application, which the agency says is needed to avoid compromising ongoing investigations, but he had not yet spoken to his client about it and did not know what position he would take.

Attempts to protect undercover officers have become common in recent Canadian terrorism cases, most recently this month’s convictions of Raed Jaser and Chiheb Esseghaier, who plotted to derail a Toronto-bound passenger train.

In that case, the FBI officer testified but the court ordered that he could not be identified. The same occurred during last year’s trial of Mohamed Hersi, a former Toronto security guard who had attempted to join Al Shabab.

Mr. Malik was arrested in Toronto on March 9 following a six-month investigation by the RCMP’s Integrated National Security Enforcement Team. He has not been criminally charged but is being detained for deportation on security grounds.

The 33-year-old Pakistani national, who came to Canada in 2004 to study at York University and was later sponsored by his wife to immigrate, is being held at a provincial detention centre while the CBSA continues its investigation.

Court records show that on April 22, 2012 he was charged by Peel police with assaulting and threatening to kill his wife. Two months later, he was arrested again for failing to stay at least 500 metres away from her home in Mississauga.

Despite the unresolved charges, he somehow left Canada, returning to Toronto’s Pearson airport on April 3, 2013. Questioned by the CBSA and Canadian Security intelligence Service, he claimed he had been teaching in Libya.

Six days later, he pleaded guilty to two of the charges and was given a conditional discharge and 18 months probation. The other charges were withdrawn. The national security investigation began the following year, in September 2014.

An undercover officer posing as a former fighter in the Bosnian civil war initially contacted Mr. Malik about installing hardwood floors in his home. According to the CBSA, Mr. Malik began to trust the officer and opened up to him.

Mr. Malik told the officer he had been to weapons training camps in Libya and supported the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham as well as Al-Qaeda, the CBSA said. They watched videos of ISIS beheadings and Mr. Malik voiced his support for the terrorists who attacked the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris, the agency alleged.

“Mr. Malik then began to recruit the undercover officer to assist him in making an explosive device that could be detonated remotely,” CBSA officer Jessica Lourenca said at a March 11 hearing. The targets were to include the U.S. consulate and buildings in the Toronto financial district.

A YouTube page that appears to belong to Mr. Malik has been mostly inactive for several years. Four years ago he commented on a video about the Pakistan army’s storming of the Red Mosque in Islamabad, where armed Islamist militants were holed up.

“May the angels lash the faces and backs of those who perpetrated [sic] this crime when they take their souls out, may their deaths be slow and painful and may they rot eternally in hell,” he wrote. On a video entitled “best jihad nasheed [song],” he commented, “Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar.”